July 1, 2014

Published On Newmobility.com

In the heart of rural Pennsylvania, in a crowded conference ballroom filled with people of all ages and disability types, a hip-hop group from New York City brought the house down. The group, 4 Wheel City, performed gut-wrenching songs about how they became injured — gun violence — and also passed along skincare tips — “You’ve got to move if you want that pressure sore to improve/You’re in a wheelchair, you’re not dead — what?”

The afterglow from their music lingered for the rest of the 2013 Living Well With a Disability Conference. The next day, workshop and expo participants would randomly sing out, “Lift with it, lift with it … you in the manual … do a little pressure release for me …”

Was conference organizer Sarah Laucks surprised that a hip-hop group had such a positive impact on a conference whose attendees were not a typical audience? “I have never worked with a group that has such a wide base of fans,” says Laucks, who is director of education and events for the Abilities Expo. “It is so incredibly diverse it amazes me. And academics really love them, that’s unusual. I would think that’s a really hard nut to crack. They bring rap to people who wouldn’t ordinarily listen to rap — people at the Living Well conference loved the words they were using.”

In fact, before the performance began at the Living Well conference, Mario Brown, director for health sciences diversity for the University of Pittsburgh, asked to give a 20-minute presentation on the work that Pitt and 4 Wheel City did together to help reach out to young people and blacks with disabilities.

And none of this is unusual for the group. For years now they’ve brought what they call “rap therapy” into rehab settings and onto school campuses to bring hope and disability awareness to people who may otherwise never hear the message that life with a disability can be sweet.

What’s the group’s favorite audience? “I like working with the young kids because they’re so impressionable and they’re the most enthusiastic when we perform and make some noise,” says 4 Wheel City’s Namel Norris. “But all the crowds offer something different, so it’s hard to really say. We also do stuff at medical facilities and disability studies venues, and it’s wonderful, too. But I connect with the kids because I was young when I was injured. And I like when I go to a hospital like Mount Sinai and the therapist tells us a person hasn’t come out of their room since injured, but they came to see us perform and it was the first time they talked or smiled since they’ve been there — that also touches me. Me and Rick talk about that all the time.”

I Was Heading Down the Wrong Road

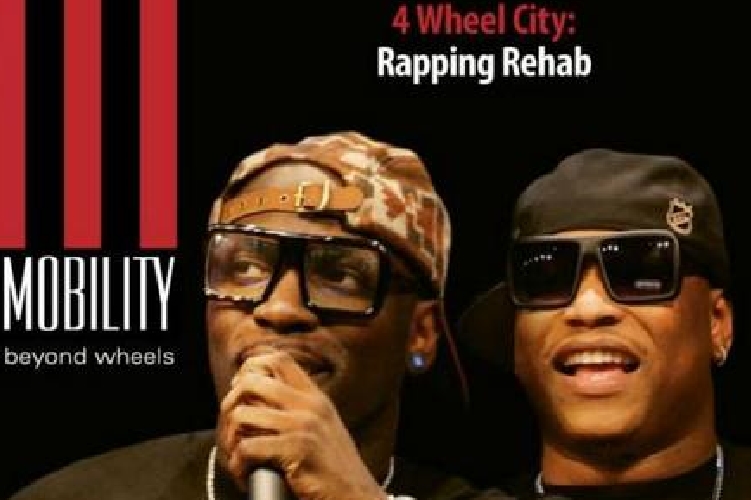

4 Wheel City has two members, Namel “Tapwaterz” Norris and Ricardo “Rickfire” Velasquez. Norris, 33, writes the lyrics and Velasquez, 38, lays down the beats. The two men have a lot in common. Both are paraplegics because of gun violence, both lived in the same Bronx housing projects, and both, before they met each other, did not know anyone else who used a wheelchair. After being injured, both felt shunned by people they used to hang out with. It was difficult “seeing how people pulled away from me — friends, family members,” says Velasquez on the group’s website. “It’s not fair.”

And both love hip-hop.

They met after Norris’ mom, Vanessa, saw Velasquez outside his building. “She approached Rick to be my friend after I came home from Burke Rehab in 1999, because she felt like he could be someone I could talk to because he was in a wheelchair as well,” says Norris, who was 17 when he was shot. “When Rick and I first met, we never cried with each other, we just worked on the music. We knew for a fact that music is very powerful and can help people.”

They met after Norris’ mom, Vanessa, saw Velasquez outside his building. “She approached Rick to be my friend after I came home from Burke Rehab in 1999, because she felt like he could be someone I could talk to because he was in a wheelchair as well,” says Norris, who was 17 when he was shot. “When Rick and I first met, we never cried with each other, we just worked on the music. We knew for a fact that music is very powerful and can help people.”

Although both men were injured by gun violence, how and why they were injured differs. Velasquez was hit by a stray bullet while walking home and still has no idea who shot him. Norris, however, was shot accidentally when a gun his cousin had acquired went off. Norris says he accepts some responsibility for what happened to him.

“I wasn’t the worst kid in the world, but was heading down the wrong road, hanging in a negative crowd, which led to a gun in my cousin’s house and what happened to me,” says Norris. “Not saying I was a bad kid, but at the end of the day I see a lot of young people going down that same road.”

This insight into his younger self informs Norris’ lyrics, as he knows he has to be his authentic self for the at-risk kids in his audiences to let him in, to let his music help them. “I see a lot of young people going down that same road, and if I’m going to go to a school and speak to a kid or someone who just got injured and they’re going to hear my story and my song, they don’t want to hear someone talk down to them, who they can’t relate to,” says Norris. So he’s real with them. “You might not like me or what I have to say, or even like my music, but you can’t say I’m bullshitting you, that I don’t know what I’m talking about, that I’ve not been through it. Especially in hip-hop, credibility means a lot.”

Norris has a huge heart for at-risk young people and describes a typical teen this way: “He’s probably going to school today debating whether he should go to class or not. Maybe he’s a weed smoker or a pipe smoker. He’s not a real bad kid at heart, but probably wants to be the coolest and is under a lot of peer pressure. He probably has a lot of dreams, maybe, but maybe don’t think they can really come true. He may be on the verge of dropping out of school,” says Norris. “That’s pretty much his mentality and so he’s probably not listening to anyone around him, and hopefully when he sees 4 Wheel City he sees himself in a few years.” Either he will see himself as possibly getting shot, or worse — dead. “On the flip side, maybe it’s possible he can accomplish his dream, like Rick and I do, and I hope they see everything is still possible with the right mentality, and everything is possible with the wrong mentality at the same time.”

Norris has a huge heart for at-risk young people and describes a typical teen this way: “He’s probably going to school today debating whether he should go to class or not. Maybe he’s a weed smoker or a pipe smoker. He’s not a real bad kid at heart, but probably wants to be the coolest and is under a lot of peer pressure. He probably has a lot of dreams, maybe, but maybe don’t think they can really come true. He may be on the verge of dropping out of school,” says Norris. “That’s pretty much his mentality and so he’s probably not listening to anyone around him, and hopefully when he sees 4 Wheel City he sees himself in a few years.” Either he will see himself as possibly getting shot, or worse — dead. “On the flip side, maybe it’s possible he can accomplish his dream, like Rick and I do, and I hope they see everything is still possible with the right mentality, and everything is possible with the wrong mentality at the same time.”

4 Wheel City’s song, “Welcome to Reality — the G-Mix” is addressed to these kids and draws on Norris’ life experiences. Featuring Snoop Dogg, the song, which can be found on YouTube, opens with the sobering fact that every nine seconds a high school student drops out. “Talking to you, mister/Mr. Knucklehead messing up in school, mister/Mr. Head to the desk with the doo-rag on, pants hanging off his ass,” the group raps. “I’m trying to open up your eyes/before you end up in jail or paralyzed.”

These guys can say this — they’ve been there, they have street cred.

“This is not just a record, it’s a movement,” said Snoop Dogg in a statement about rapping with 4 Wheel City. “It’s a feeling! I’m down with the movement, we are about doing something righteous.”

Norris acknowledges the group is pushing uphill in trying to save these kids. As he knows only too well, guns are a big part of urban culture. “Where we come from, people don’t talk things out — they shoot it out, they fight it out, and they end up in wheelchairs or dead,” he says.

And he knows it all too well.

It’s Not the Gun Itself

“To elaborate, to me guns are the problem, but they’re not the problem so much as the community,” says Norris. “The problem is the mentality of young people in the community that I come from wanting to be bad and cool and tough. It’s almost like a checkpoint that you have to pass through to become a man. That mentality is the worst part about the whole thing — most kids go to jail because the guns aren’t legal and they’re shooting each other over dumb stuff. Why would a young person want to have a gun in the first place? Back in the day it used to be bats or knives, but guns are so easily available. And if you have a gun it’s like you’re cool and you’re bad. And who doesn’t want to be cool and bad?”

Getting shot and paralyzed turned his life around to where he’s an excellent role model for young people, but Norris says it doesn’t have that effect on everyone.

“Some be like, ‘you don’t mess with guns now, because you got shot and that’s your story, you learned your lesson.’ But I know some who got shot and went back to the same life,” he says. “But when I started going to school, I realized I could be the same person, be aggressive and go get things on a cleaner, higher level.” Norris earned his bachelors in business from Lehman College in 2006.

Velasquez also has strong feelings about guns. “I hate guns,” he says bluntly. “We have to get rid of all of them. Who needs guns?” But like Norris, he thinks that guns, inanimate objects, of themselves cannot do anything. “It’s the people,” he says. “But what are they using them for? You might want to shoot somebody and miss your target — that’s what happened to me. I’m sitting here, and I had nothing to do with guns.”

Velasquez never wanted anything to do with street life. His mother, Maria, brought her family up from Honduras when he was 15 in pursuit of the American dream. A high school senior at the time of his injury, he says, “My story is the opposite of Tap’s. I was going to school and was working a little part-time job when I got hit by a stray bullet. I still don’t know who shot me. It turned into the American nightmare. But I’m here, I’m still breathing, I have my brother, Tap, and life is good. You’ve got to keep going.” Velasquez is a stay-at-home dad with his 3-year-old daughter, Cleo, and also has a son who’s getting ready to go to college.

A fluent Spanish-speaker, Velasquez says he identifies as black more than Latino, “because when you see me that’s what you see.” And speaking of race, the duo understands the ground they’re breaking for other black artists with disabilities. “You don’t see hardly anybody doing what we’re doing,” he says. “You might see some musicians with disabilities, but it’s not usually a black person. We’re going to change that little by little. Might take a hundred years, but we’re doing the right thing right now,” he says.

Hip-hop Can Unite Us

Many wheelchair users of all races report feeling like they’re the only one, isolated. There’s a dearth of role models for everyone, but it’s especially pronounced for blacks who use wheelchairs. Also, getting young people with disabilities involved and informed is a perennial struggle. Fortunately, both of these populations have an affinity with hip-hop music and culture. This is what made 4 Wheel City’s collaboration with the University of Pittsburgh such a good model for diversity outreach.

Lester Bennett, a grad student at Pitt, was instrumental in bringing the group to the university. Bennett, a T10 para as a result of a gunshot, also was employed by Three Rivers Center for Independent Living at the time. He and the CIL, together with Pitt and 4 Wheel City, created a diversity program with hip-hop and other arts as the centerpiece.

Was it successful? Oh, yes, very much so.

“4 Wheel City was the key,” says Bennett. “They were the key to the young people who say, ‘this isn’t for my parents, they’re talking to me.’ And key for African Americans who say, ‘they look like me and they are into the same things as I am.’ Both demographics we wanted to target with outreach see themselves in 4 Wheel City.”

Bennett’s being a para from a gunshot helps him identify strongly with the group. On April 22, 1994, he was approached by muggers while out on the town. “Before the robbery attempt, they sparked up conversation with us,” he recalls. “What are you doing with these white girls? That was their first statement. When the guy pulled the gun out, at first I couldn’t do anything because I was so angry that they brought race into it. My stepmother was white and I was raised to treat people equally,” says Bennett, who is black. “Then they pulled that gun out on me and I reached for the gun. I wanted to smack it out of his hand, and he pulled the trigger, then two more times. But he didn’t aim at my head, so he didn’t intend on killing me.”

Bennett’s being a para from a gunshot helps him identify strongly with the group. On April 22, 1994, he was approached by muggers while out on the town. “Before the robbery attempt, they sparked up conversation with us,” he recalls. “What are you doing with these white girls? That was their first statement. When the guy pulled the gun out, at first I couldn’t do anything because I was so angry that they brought race into it. My stepmother was white and I was raised to treat people equally,” says Bennett, who is black. “Then they pulled that gun out on me and I reached for the gun. I wanted to smack it out of his hand, and he pulled the trigger, then two more times. But he didn’t aim at my head, so he didn’t intend on killing me.”

Being a black man disabled by a gunshot carries a stigma with it, which Bennett understands professionally as well as from a personal perspective.

“There’s a young guy who just got shot by some police officers here in Pittsburgh. I want to advocate for him, but I don’t know what he was doing to put himself in that situation,” says Bennett. “So, yes, there is a stigma. I know from how people deal with me and how I look at him. It doesn’t make it right, but we’re human beings and all come with our own biases.”

Bennett feels events like the one that brought 4 Wheel City to Pittsburgh can foster unity among people with disabilities. “Hip-hop has been around all our lives, so it’s not even a black thing anymore. It’s an urban thing that’s even reached the suburbs, so it’s a thing that can unite us,” he says. “And what 4 Wheel does with disability is they show we all have a lot of things in common that we can discuss in an open forum where we’re not throwing stones at one another. We have differences, but we must acknowledge our similarities.”

Hip-hop absolutely has the power to cut across demographics and reach younger people, says Pitt’s health sciences diversity director Mario Brown, agreeing with Bennett. “One of the planners of the event that brought 4 Wheel City to town just recently talked about a student wheelchair user who goes to a mainstreamed school,” he says. “He brought some of his classmates to the concert and they really loved it, and you could see how proud he was that he turned them onto them. He just felt so good about himself. It’s not that anyone had been treating him bad, but no one had been paying him any attention at all, so he became the cool guy for a few minutes.”

As expected, the event helped disability organizations reach underrepresented populations of people with disabilities. In fact, it spurred a flurry of grant proposals focusing on hip-hop as a way to reach deep into various populations of people with disabilities.

But another happy outcome is that it has also spurred Pitt to start appointing people with disabilities to committees that don’t necessarily have a disability focus. “I coach a community research advisory board to look at racial and ethnic health disparities, and as a result of the event that brought 4 Wheel City in, I realized we didn’t have anyone representing the disability movement,” says Brown. “So I asked Lester and another wheelchair user to sit on that board.”

And also, bringing in a hip-hop group from New York City spurred the university to think of other unique ways to enhance outreach to people with disabilities. “When the Pittsburgh Jewish Film Forum sponsored Reel Abilities, our office was front and center to review films and promote the disability film festival that took place at various venues around the city,” says Brown. “We were able to participate in that as a result of the 4 Wheel City event. There’s always more work to be done, and the thing is how do you measure the effect that you have, which usually takes money and human capital. Has what you’ve done made any impact? But people who weren’t talking about disability are talking about it now.”

It Started With a Song

James Cesario, senior outreach program coordinator of rehab medicine for New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital, helped give 4 Wheel City their start. Norris would come to a weekly transition group offered by Mount Sinai’s rehab to meet with those who were still in rehab, to provide peer support. “One time he said he writes songs and raps. So everybody prompted him to demonstrate. He pulled one out and it blew everyone away. It was about his mom, what she meant to him,” says Cesario. “I said, ‘you have a real talent, we have to get you involved with us!’”

Invited to write a rehab-themed song, Norris and Velasquez put their heads together and came up with “Pressure,” about the importance of pressure release to prevent decubiti. Cesario had it made into a CD that included skin care tips on the back of the jacket and started passing it around. Cesario says he also encouraged the two men to keep getting out into the community, to spread their message — especially about educating kids about violence and staying in school. “They hooked up with some people and started getting bookings with high schools, telling the kids, ‘so you think you’re cool, well you’re not cool,’ and they tell their story. It has reached out and touched a lot of kids.”

As a rehab professional, Cesario, who was injured at the T4 level 40 years ago, knows it’s important for people who are newly injured to be able to connect with peers. “I’m older, I’m white, I’ll give them the right stuff, but Namel can reach a whole different group of people than I can. There are so many people who’ve been shot or stabbed, who come from dysfunctional families. Namel is more powerful than me because he’s been there, and they’re going to listen to him and like him,” he says. “Look what he’s doing, opening up an area of music. They can identify.”

Cesario has provided the group with a venue to perform and also was able to get the New York City chapter of the National Spinal Cord Injury Association to present them with a sound system. “From time to time I’ll call them and ask if they can come in and perform, and they’ve gotten better over the years. Also, if I have a guy in rehab that I think they’ll mesh with, I’ll call them, and they’ll come bedside.”

From performing at Mount Sinai and schools in New York City, 4 Wheel City expanded its reach and began marketing its program to universities that have an interest in disability issues such as Pitt. Most recently, James Madison University hosted the group as part of its fifth annual Disability Awareness Week. And the group even performed in London at the beginning of the 2012 Paralympics.

“What surprises me and makes me proud is that we’re reaching all types of people. We never thought we’d be performing at disability studies conferences, for example — we didn’t even know those things existed. We were just trying to give a voice to our community,” says Norris. “We just telling our story and knowing people can relate to it. Now that we see it is actually real, it is something we are very proud of. It will take a little while for the hip-hop community to catch on, but we feel we are giving a very positive message for hip-hop as well.”