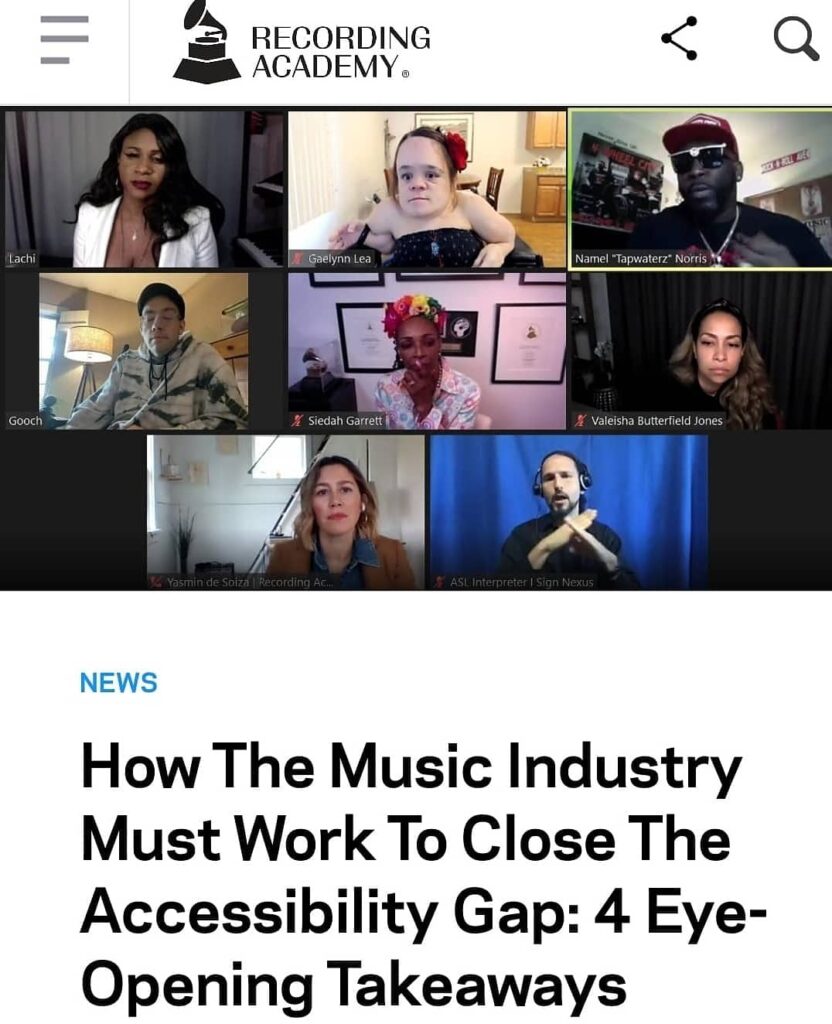

Fitting perfectly with April’s “Celebrate Diversity Month” theme, last month, the Recording Academy’s New York chapter hosted Music, Purpose + Community: Highlighting Creators Working to Close Accessibility Gaps On and Off the Stage, an hour-long panel highlighting the challenges musicians with disabilities face on a regular basis as well as the urgent necessity to close the accessibility gap. The panel, which marked the Recording Academy’s inaugural event focusing on accessibility, implemented accessibility features like live interpretation and transcription services, also a first for the organization.

Moderated by recording artist, songwriter and disability inclusion advocate Lachi, the panel comprised violinist/songwriter and NPR Music’s 2016 Tiny Desk Concert Contest winner Gaelynn Lea, GRAMMY winner and two-time Oscar-nominated songwriter Siedah Garrett, singer/slide guitarist Ryan “Gooch” Nelson), hip-hop artist and motivational speaker Namel “Tapwaterz” Norris and the Recording Academy’s Chief Diversity & Inclusion Officer Valeisha Butterfield Jones.

The event examined the challenges musicians with disabilities face in the music industry, including stigma, lack of opportunities and inaccessible venues. WATCH BELOW.

Lachi, who is legally blind, opened the program discussing her desire to become the very role model she lacked when she was growing up. “I grew up as a blind kid, and I was passionate about music and entertainment, but I didn’t have a lot of folks who looked like me and had my situation,” she said. “It made it really difficult for me to have an ‘I want to be that’ type of goal, to find identity, especially in music specifically … I want to be the role model that the industry hasn’t seen in folks with disabilities. I want the industry to foster and promote such role models because the next generation absolutely deserves it.”

Garrett, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) seven years ago, talked about how she moved past her fear of disclosing her illness and potentially losing opportunities. Similar to Lachi, Garrett wanted to inspire. “When I was first diagnosed, I was so afraid I didn’t tell anyone for a long time, not my friends, not my family, and especially not my peers,” she said. “I didn’t want to be looked at as someone who was disabled because there’s an automatic analogy of who you are and what you can do, and if they don’t want to be bothered with your accommodations, then you don’t get called for that gig or considered. So I didn’t want to let anyone know I had an issue, but I decided if I was quiet, then no one would know my story and I wouldn’t inspire anybody because I was hiding,” she said.

Lea, who was born with osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a congenital disability, spoke candidly about the challenges she’s faced in a wheelchair due to the ubiquitousness of venue inaccessibility. “The places I can play are extremely limited. This is a huge issue that a place like the Recording Academy really can be taking the lead [on], because the reality is, with so many venues, I can’t get in the door, I can’t use the bathroom, I can’t get to the room where the stage is, and that’s just if I want to attend a show,” she said.

“If I want to perform at a show, a lot of the time, I can’t access the stage because there’s no ramp. The green room is not even on my radar right now because it’s so difficult to find the basic accessibility requirements … So the reality is, the barrier to entry is so high right now. It’s a really urgent problem.”

Nelson, who became quadriplegic after an accident toward the end of high school, relearned how to play guitar with paralyzed hands. He echoed Lea’s experiences, relaying an anecdote about a live show years ago. “I travel around in a power wheelchair, so it’s big, it’s heavy, it’s hard to get on stage,” he said. “I remember back when I first started out, I went and saw Robert Randolph play. And he jumped off stage, and he invited me up to play with him, but there was no ramp to get on stage. And so he and his bandmates tried to lift me up onto the stage, almost dropped me and ended up sitting on the ground in front of the stage, and they ran a guitar cable out to me.”

Norris co-founded 4 Wheel City, a hip-hip duo and movement, with Ricardo “Rickfire” Velasquez. Norris became paraplegic when his cousin accidentally shot him, and Velasquez developed paraplegia after being hit in the street by a stray bullet. The pair created 4 Wheel City to inspire change, create more opportunities for people with disabilities and encourage at-risk youth to stay away from gun violence.

Norris said when he was first in a wheelchair, he thought he couldn’t rap anymore “because hip-hip is very masculine and everything,” he said. But taking a cue from Stevie Wonder, Norris decided to keep playing music. He started to wonder why no one was talking about disability and made a pact to become “unapologetically disabled,” promising to break down barriers.

Butterfield Jones cited a statistic from the Harvard Business Review, which noted that while 90 percent of companies say they prioritize diversity, equity and inclusion, only four percent of them consider disability to be a priority. “We have the power to change that and do that now in the music industry,” she said. “Not only am I committed to doing the work we need to do for creators with disabilities at the Recording Academy, but let’s roll up our sleeves and lock arms with the [record] labels and touring companies and digital streaming services to also make sure we’re doing this together.”

To recap the informative conversation, and four key takeaways from the Recording Academy’s Music, Purpose + Community panel. CLICK HERE!

TO RECAP THE CONVERSATION & READ MORE OF THE ARTICLE ON THE RECORDING ACADEMY’S / GRAMMYS WEBSITE CLICK HERE! OR FOLLOW THE LINK https://www.grammy.com/membership/news/how-music-industry-must-work-close-accessibility-gap